By and for the people: Social innovation, technology and diversity shifting the practice of law

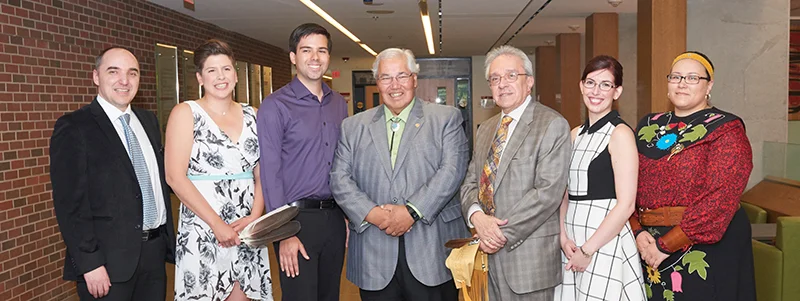

Osgoode Hall Law School held its first annual Honour Ceremony for indigenous graduates in 2015 as part of Spring Convocation celebrations. Pictured are five of the eight indigenous graduates of the Class of 2015 with Justice Murray Sinclair (LLD ‘15) and Justice Harry LaForme (LLB ‘77), (LLD ‘08). From left to right: Joshua Tallman, Serena Dykstra, Jacob Dockstator, Justice Murray Sinclair, Justice Harry LaForme, Kendra d’Eon, Laura Mayer. Photo: Ian Crysler

A Q&A with Lorne Sossin, the Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School. A law clerk to former chief justice Antonio Lamer of the Supreme Court of Canada and a former associate in law at Columbia Law School at York University, he was also a litigation lawyer with Borden & Elliot (now Borden Ladner Gervais LLP). Dean Sossin shares his perspective on the nature, direction and potential impact of legal innovation in Canada.

What are some of the primary ways that innovation is changing the practice of law today?

The great, disruptive potential of technology is coming late to our sector, but it’s coming – everywhere – to reshape how we think about law, how legal services are delivered and how legal problems are solved.

“We used to see law as a courthouse and a group of people in robes, most often white males. Now we’re seeing a diverse judiciary and more diverse dispute resolution options such as mediation and negotiation.”

This year, for example, we’ve seen the first entirely online statutory tribunal, which will help people solve disputes involving condominium and small claims complaints in British Columbia. It’s the first edge of a large wave that will ensure we approach law the same way we do so much else in our lives – on our phone, at our convenience, with full accessibility, in whatever part of the country we live in, whatever type of problem we have.

That is the consumer experience people now expect, so there is lots of pressure to have our experience with government and the dispute resolution sector flow from that expectation.

If I were to capture it in one sentence, it is beginning to look at the justice system as designed by and for the people who use it rather than by and for just lawyers, judges and experts.

That will also change the kinds of lawyers and legal professionals that we’re training, of course.

You’ve written in the past about social innovation in law – what are some of the ways this shift is translating into practice and outcomes?

Beyond technology, the other side of legal innovation is the way law is coming to terms with better adaptations to our humanity and to the way that we live.

Perhaps the most influential example here in Canada is looking at the legal system through the lens of reconciliation, seeing the ways in which law has been part of the problem in our relationships with indigenous communities, and how it can now be a driver of reconciliation and solutions.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission came out of the big class-action lawsuits that were settled. It’s a great standard bearer for the idea that we can do law in a way that responds to the human need to be heard, to have the fullness of one’s life validated and understood. We see it in the indigenous community, in our mental health and law sector, and in family law and child welfare.

As much as technology can help us seamlessly access legal services and solve problems more quickly and efficiently, and drive new economic activity, law is also responding in innovative ways to the challenge of reaching out to ensure marginalized and vulnerable people see it as empowering, protecting and supportive, not as a kind of remote force of authority in their lives. Which, for many, is certainly the way it has been in the past.

We used to see law as a courthouse and a group of people in robes, most often white males. Now we’re seeing a diverse judiciary and more diverse dispute resolution options such as mediation and negotiation.

How will these shifts change the nature of legal education in Canada?

Each school will do this in a different way, with its own style and approach. But we’re moving away from the idea that you come to law school, learn about legal doctrines and ideas, and write papers to show you understand them. That model was an innovation a century ago, but it is now giving way to the problem-solving approach.

For a problem solver, knowledge of law and analysis of law’s contexts are vital points of departure, but how you put law into action is equally important. There is now a lot more emphasis on experiential education, where students apply ideas in real-world situations. That may be clinical programs, externships, placements or co-ops. It might even be simulations, structured in ways that students have a real learning journey. It’s all aimed at a marriage of theory and practice, seeing law as a set of ideas about justice and putting those ideas into action and, if necessary, going back to rethink the ideas when they don’t work for people in practice.

It is also focusing on reflection: creating a group of leaders who have the emotional intelligence to listen to and learn from their clients and the communities they serve and then ultimately to be agents of change and proponents of law reform. In other words, being not just the doers but also the thinkers – and not just the thinkers but also the doers.

For more related to this story visit globeandmail.com