Future of farming

What made-in-Canada food stands for

When John Jamieson travelled to Qingdao, China, on a trade mission a few years ago, he was surprised to see numerous food items labelled in English and accompanied by the icon of the Canadian flag in the supermarket. In response to his query, a Chinese colleague informed him that made-in-Canada products were very popular with local shoppers.

This high regard for Canadian food was also reflected in a 2014 Conference Board study on the food safety performance of 17 OECD countries, where Canada – together with Ireland – received top grades relative to their peers.

“When people see the Canadian flag, they associate it with food quality and safety,” says Mr. Jamieson, CEO of the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity (CCFI), who sees this as good news for Canadian farmers, 90 per cent of whom depend on exports, and for a sector that exports $56-billion a year in agriculture and agri-food products.

Mr. Jamieson, who previously worked as a deputy minister for agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture for Prince Edward Island (PEI), adds that the experience in China illustrated “how valued and recognized the Canadian brand is internationally.”

“We need to think about food production and processing, but also about distribution and consumption. The discussion often revolves around feeding a growing global population – having too many people and not enough food – but that’s not the issue in Canada. ”

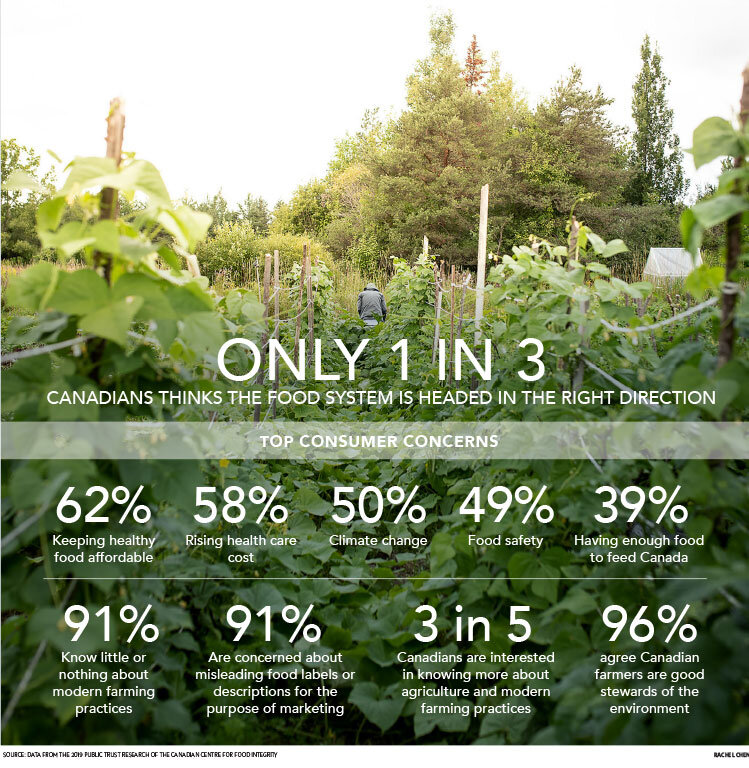

However, a recent CCFI study shows that Canadian food doesn’t inspire the same consumer confidence closer to home. While approximately three in five Canadian consumers view agriculture in Canada positively, only one in three believes Canada’s food system is headed in the right direction.

To Mr. Jamieson, “this doesn’t come as a surprise. Today, we are much more removed from our food production than 40 or 50 years ago, and Canadian farmers now make up only two per cent of the population.”

According to the survey, 91 per cent of Canadians claim they know little, very little or nothing about modern farming, he says. “Getting bombarded with a mass of information about food production – some of it conflicting – raises questions about modern farming practices and technology, and consumers are looking for answers.”

One of the messages he’d like to convey is that “the people in our farming and food production community and Canadians are on the same page when it comes to working to ensure everyone has access to sufficient safe and healthy food.”

Yet while Canadians, on average, spend nine per cent of their income on food – a percentage that is much lower than in most parts of the world – four million Canadians still live in food insecurity, says Gisèle Yasmeen, executive director of Food Secure Canada (FSC). “The primary reason is poverty, where people are not able to afford food due to the gap between income and cost of living.”

Canada has committed to meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, which include eradicating hunger, says Ms. Yasmeen. “We only have 10 years to get there.”

Canada’s national food policy, launched in June 2019, represents “a big step forward,” but Ms. Yasmeen suggests more needs to be done. “We need to think about food production and processing, but also about distribution and consumption,” she says, adding that a recent study shows that 58 per cent of food produced in Canada is wasted. “The discussion often revolves around feeding a growing global population – having too many people and not enough food – but that’s not the issue in Canada.”

Instead, structural barriers affect our ability to address issues like affordability, food waste and sustainability, and Ms. Yasmeen calls for solutions that “go beyond industrial food systems to move towards ecological and regenerative agriculture. We also need to think about health outcomes.”

The new Canadian food guide recommends that half of our plate should be filled with fruit and vegetables, one-quarter with protein and one-quarter with whole grains, says Ms. Yasmeen.

Heart & Stroke research estimates that diet-related disease costs the Canadian economy $26-billion a year, she says. “Rising consumer awareness means we are moving away from the industrial diet and ultra-processed food. However, we need to ensure fresh fruits and vegetables are not becoming luxury items for low-income families.”

While consumers’ food choices can contribute to a shift towards sustainable food production, institutional support is essential for achieving system change, says Ms. Yasmeen. For example, FSC is hosting the Coalition for Healthy School Food to advance a national school food program.

“We need to enlist schools, hospitals and governments as allies for stimulating demand for healthy food produced in an environmentally sustainable way,” she says. “Partnerships and community engagement are important, and the public, private and non-profit sectors all have a role to play. We have to look at our food production potential, now and in the future, and think about protecting the health of our soil and water and our biodiversity.”

Mr. Jamieson believes science and technology can help to advance sustainable farming practices. “Many consumers are concerned about things like pesticides and fertilizers, but precision agriculture is already helping to reduce [agricultural input] significantly. And our understanding of soil health has never been greater. Potato farmers in PEI, for example, grow mustard and plow it into the soil to combat wireworm.”

In response to survey findings, the CCFI has identified three priority topics for consumer engagement: climate change, food safety and health, and science and technology, says Mr. Jamieson, who sees transparency as key. “Consumers want an industry that is open about mistakes and committed to improving practices. They also want to hear from farmers to know they take climate change seriously and work to advance sustainability.”

For more stories from this feature, visit globeandmail.com